In Mark Cline’s world, every day is an adventure and anything imaginable is possible. So when Cline got the idea to build a life-size replica of Stonehenge out of Styrofoam, he didn’t think twice about making it a reality.

He purchased several massive pieces of foam, painted them gray and stood them in a field in Natural Bridge, Va.

Ta-da, Foamhenge!

And when he envisioned an attraction that entailed dinosaurs devouring Yankee soldiers, Cline went ahead with that, too.

He crafted a series of creepy scenes. Among them, a gang of raptors surrounding an unsuspecting cow, a dinosaur bursting out of the ground with its jaws wide open and a T-rex stalking a trembling soldier.

He fashioned each fiberglass dinosaur to look as authentic as possible, staged the scenes along a walking trail and named the attraction Escape From Dinosaur Kingdom.

“I’m just following a dream,” Cline said in a rambling fashion. “One dream just leads to another dream.”

A Childhood Fantasy

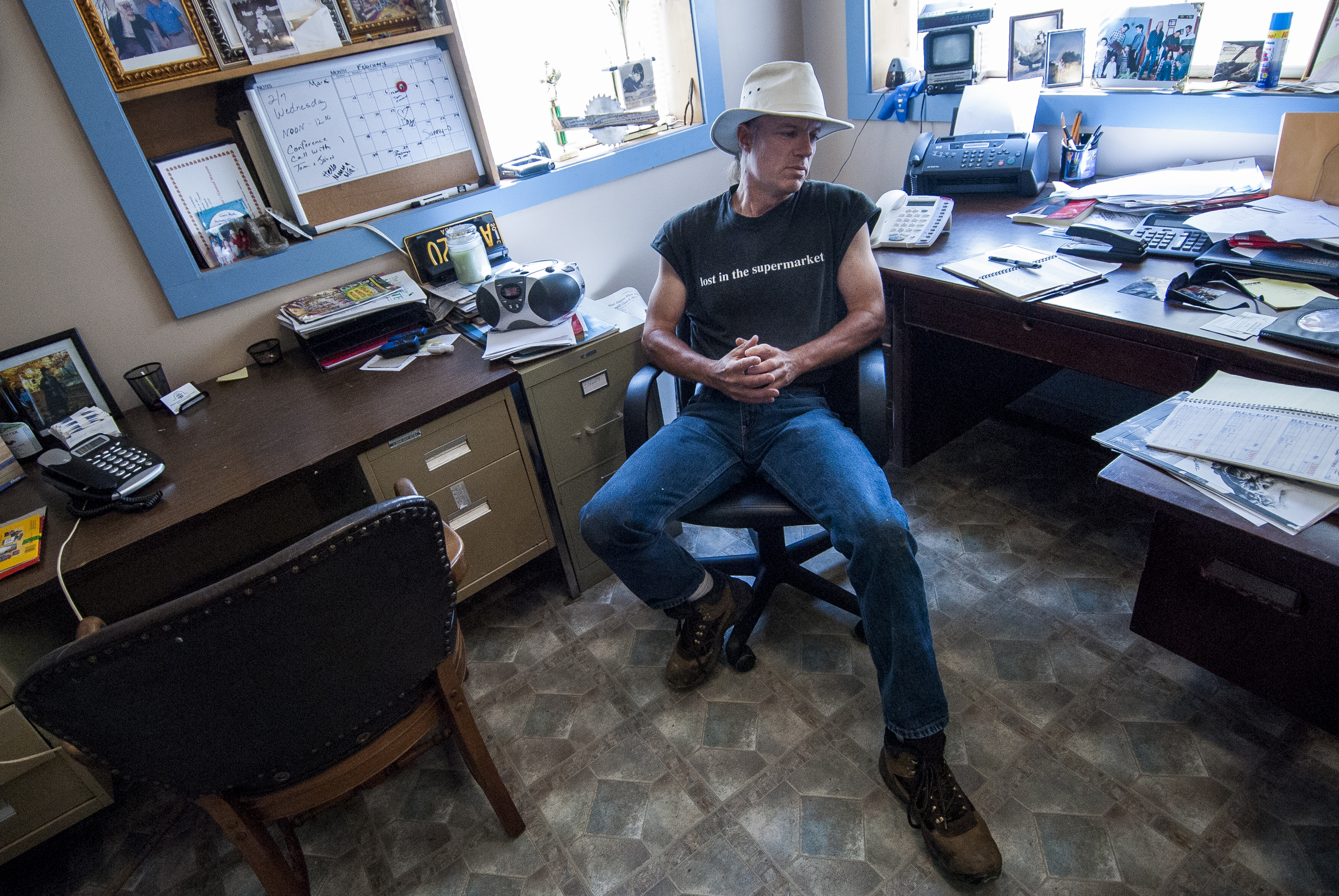

Cline, 46, sits in a small desk chair in his office. Behind him is a black and white picture of himself as a young boy working on a drawing. He points to the picture and admits he didn’t do well in school and had no intentions of attending college. Art was his greatest enjoyment.

“You didn’t want to be an accountant, did you?” Cline shouts at his childhood photo. “I’m doing it for that kid.”

It’s that kid that conjured the dream to spend his adult life building fiberglass creations.

Cline was riding in the car with his dad one day near White Port, Va., when they saw a sign for Dinosaur Land. Cline begged his dad to stop, but when they pulled in, the place was closed. As Cline peered through the fence at the display of faux dinosaurs, he declared to his dad that one day he would make similar sculptures.

“I basically said to him, ‘I’m going to build these when I get older,’” Cline said. And “he said, ‘If that’s what you want to do, nothing’s going to stop you.’ Those words were so important to me. That really enforced the dream.”

Cline opens the door to his workshop, Enchanted Castle Studio, and a fantasyland appears.

The warehouse-like building is packed with wacky creatures, including an 8-foot tall Yogi Bear, a life-size elephant and a giant Herman Munster. Known as a “fiberglass wizard,” Cline can craft nearly anything from the durable material. All it takes is a bit of imagination and a lot of talent, neither of which he lacks.

“I’m 24 hours of nothing but creativity,” said Cline, an intense gaze in his olive-green eyes. “I’m always going.”

Pursuit Of Happiness

It took Cline, the son of an electrician and a secretary, a while to realize his ambition.

After graduating in 1979 from Waynesboro High School in Waynesboro, Va., Cline lived “kind of like a bum.”

He rode a raft down the Missouri River like Huck Fin and traveled around the country taking in the sights until he finally returned to Virginia.

Now what? Cline thought, as he sat in a park one day and wrote in his journal about what he wanted out of life.

“Sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll? No, those things are superficial,” Cline recalled thinking. “I wanted what everyone wants. Everyone wants to be happy.”

The first step toward happiness was finding work. Cline went to the employment office and asked the woman behind the counter if she had any jobs.

“I said, ‘I’ll do anything,’” Cline recalled.

To Cline’s dismay, the woman didn’t have anything to offer him. But as Cline turned to leave, the woman got a phone call.

“I had my hand on the door,” said Cline, jumping up from his seat to grab the knob on his office door. “She said, ‘Wait, I have something.’”

The job was with Red Mill Manufacturing, a company that made handcrafted knick-knacks in Fishersville, Va.

Cline accepted the position without hesitation. His job at the small factory was to mix the resin that was used to make the figurines, which were often in the shapes of teddy bears, birds and people.

One day, Cline’s boss asked him to stay after work. “He said, ‘I’m going to teach you how to make a mold of your hand,’” Cline recalled. After demonstrating the basics of mold-making, the boss gave Cline a 5-gallon bucket of resin to take home.

Cline played with the resin and used it to make a few monsters, his fascination at the time. It was a breakthrough in getting his sights back on his childhood desire.

“It was like a revelation,” Cline recalled. “I always knew I could do this, but I just didn’t know how.”

‘Natural High’

In 1982, Cline moved to Natural Bridge and opened a haunted house. He thought the attraction would be a hit with tourists who frequent Natural Bridge, a nearby rock formation once owned by Thomas Jefferson.

He was wrong.

After two years the house wasn’t making any money and Cline’s outlook on life took a downward turn.

“I had tremendous depression at 24,” Cline recalled. “I let peer pressure get to me. I was thinking I should be here by now. I felt like I was a failure.”

Feeling like he had nothing to live for, Cline climbed to the top of a mountain and prepared to jump off. But when he looked out at the view, his mind-set changed rapidly.

“I had this 10-minute natural high,” Cline recalled, stretching out his arms. “I was baptized in the Church of Christ in 1970, but this was a true baptism. I was back on track. I wanted to be a happy person.”

Cline set out to sell his work. Knowing it wouldn’t be easy to sell giant monster figurines in the rural area, Cline decided to paint signs instead. The only problem was he’d never painted signs before and didn’t have any examples to show his potential clients. It was an issue Cline remedied by taking pictures of other people’s signs and subtly touting them as his own.

“I’d say, ‘Do you like this sign?’” said Cline, motioning as if he was showing a picture from his portfolio. “Then I’d ask them if I could paint their sign.”

Whenever he finished a sign, Cline took a picture of it. Gradually, he replaced the photos in his portfolio with images of his own work.

The more work Cline got, the more elaborate the signs became. He began adding fiberglass figures to make them more original.

“As I got good at it,” Cline said, “the signs became smaller and the statues became larger.”

Dream Come True

Cline transformed his failing haunted house into a fairytale castle where he could take his dream to the limits. Complete with towers and wonderland creatures, he called it Enchanted Castle Studio after an amusement park he went to as a kid called Enchanted Forest.

“We didn’t have a lot of money, so [Enchanted Forest] was sort of our Disneyland,” Cline said. “But I didn’t know that when you grew up you didn’t have an Enchanted Castle, so I built one.”

Cline opened the studio to tours, which not only gave him a opportunity to show off his work but also allowed him to ham it up by entertaining guests with impersonations of Mick Jagger and Barney Fife.

“I’ve just always had a real love for entertaining folks,” Cline said. “If they smile and laugh, that’s healing.

To further market his work, Cline attended trade shows and networked with other people in the industry.

Cline soon began winning commissions from major corporations, including Six Flags Theme Parks, Putt-Putt Inc., Johnny Appleseed Restaurant Chain and Jellystone Park Campgrounds. He even landed work with the place that sparked his interest in fiberglass creations as a child, Dinosaur Land.

“The dinosaurs we had before Mark started making them were more like statues,” said Joann Leight, who owns Dinosaur Land with her sisters. “The ones that Mark makes for us interact with the environment more, like we have one that looks like it’s eating out of a tree. His have more action to them even though they don’t move. He’s a real creative guy.”

Some people don’t think as highly of Cline’s handiwork.

In 2001, someone set fire to Cline’s Enchanted Castle and left a note in his mailbox that accused him of being part of a satanic cult.

“It said I was doing the work of the devil, and I needed to be destroyed,” said Cline, shaking his head. “I’m out here in the open. You can look at it and like it or look the other way.”

Losing his castle and many of his creations to the fire didn’t stop Cline. He rebuilt his studio, although this time much less ornate, and kept right on working.

At the request of the owners of Natural Bridge, Cline converted a turn-of-the-century mansion, located near the tourist attraction, into a haunted house called Dr. Cline’s Haunted Monster Museum.

In wake of the haunted museum’s success, Cline built Dinosaur Kingdom next door and Foamhenge just down the road. He also created other tourist attractions, including Professor Cline’s Time Machine and Capt. Cline’s Pirate Adventure Ride, both in Virginia Beach, Va.

These days, Cline continues to do a lot of work for theme parks and tourist traps. He also makes quite a few sculptures for individuals.

“I made one of those for Alice Cooper,” said Cline, pointing to a giant skull on the outside of his haunted museum. “I do a lot of work for these eccentric rich people.”

The Hero

Back at his studio, Cline maneuvers through piles of fiberglass dinosaurs, robots, wizards and other creatures before getting in a beat-up pickup truck and whizzing down the road to Foamhenge.

Standing amid the Styrofoam columns, Cline talks about his plans to add fiberglass statues that tell the “legends of Foamhenge.”

Just as he starts to explain where the mammoth Merlin will be positioned, a group of day travelers make their way up the hill. Cline immediately engages them in conversation.

“How do you like England?” he asks.

“If I would have known it was so close, I would have come a long time ago,” said Dawn Snipes, of Bentonville, Va. “Is this yours?”

“That depends,” Cline replies. “Do you like it?”

Snipes shakes her head yes. “Well then, yes,” Cline said.

“You should go to Hollywood,” Snipes said. “This is great.”

Cline smiles. He’s heard that line many times before. But for a man who has no idea how much money is in his bank account, (his wife takes care of the finances) Hollywood is not part of the plan.

“Why would I do that?” asks Cline, motioning toward the panoramic view of the Blue Ridge Mountains. “Look at this.”

After posing for a few quick pictures with his guests, Cline heads back to his studio, where a few unfinished dinosaurs await. It’s time to get back to the dream.

“You’ve got to be the hero of your own adventure,” Cline said. “Otherwise, the comic book’s not worth reading.”

Pete Marovich is a photojournalist based in the Washington D.C. metro area covering the White House and Capitol Hill. He is co-creator of American-Journal Magazine and serves as photo editor.

Pete Marovich is a photojournalist based in the Washington D.C. metro area covering the White House and Capitol Hill. He is co-creator of American-Journal Magazine and serves as photo editor. Jenny Jones is the editor and co-creator of American-Journal. She has more than 15 years of experience working for daily newspapers and monthly magazines. She is a freelance writer based in Virginia.

Jenny Jones is the editor and co-creator of American-Journal. She has more than 15 years of experience working for daily newspapers and monthly magazines. She is a freelance writer based in Virginia.

Leave a Reply